The "Thirteen Towers" of Chankillo (Peru): Solar Observations & the Legitimization of Power in an Early Complex Society 400 BC

Dr. Ivan Ghezzi

This is Dr. Ivan Ghezzi extracting something at Chankillo. Chankillo was not studied until he had the bright idea to do it, even though people have known about it since the 1800s. He is Peruvian but was educated at Yale. Yup.

This is Dr. Ivan Ghezzi extracting something at Chankillo. Chankillo was not studied until he had the bright idea to do it, even though people have known about it since the 1800s. He is Peruvian but was educated at Yale. Yup.Dr. Ghezzi first outlined what exactly an observatory was and what astronomical alignment was. Observatories are places built purposefully to observe solar, lunar, or other celestial occurances. Astronomical alignment is when a building or group of buildings are aligned to fit some celestial occurance (equinoxes, eclipses, sunrise, etc). It may have to do with calenders, religious celebrations, or whatever, but it is on purpose. A lot of the time archaeologists see that something could make sense one way, so they decide that that is how it was, and all evidence they find they make to fit their theory until it doesn't work anymore.

For instance, the main guy (can't remember his name, but he also worked with Dr. Ghezzi on the Chankillo project) of archaeoastronomy has proved that Stonehenge has little to nothing to do with astronomy of any sort. It is not a calender.

I'm still having a hard time believing this, but I guess I should take the word of the educated man. Also, the Nazca Lines, the giant drawings people think are either calenders or ancient crop circles, are neither. When examined closely, the lines are oriented in virtually every conceivable direction, so there is no way they could be a calender or anything like it.

I'm still having a hard time believing this, but I guess I should take the word of the educated man. Also, the Nazca Lines, the giant drawings people think are either calenders or ancient crop circles, are neither. When examined closely, the lines are oriented in virtually every conceivable direction, so there is no way they could be a calender or anything like it. It made me start thinking about other places, like the tilted archway thingo at Tulum that the sun shines through only on the morning of April 6, but I'm pretty sure that one is still on purpose. It's just too much of a coincidence.

It made me start thinking about other places, like the tilted archway thingo at Tulum that the sun shines through only on the morning of April 6, but I'm pretty sure that one is still on purpose. It's just too much of a coincidence. (This is a guy holding a picture of the sunrise at Tulum. The actual building is difficult to find a picture of...) Actually, there it is on the left there:

(This is a guy holding a picture of the sunrise at Tulum. The actual building is difficult to find a picture of...) Actually, there it is on the left there: Anyway, the point is that the ruins at Chankillo are definitely purposefully astronomically aligned.

Anyway, the point is that the ruins at Chankillo are definitely purposefully astronomically aligned. Specifically, it is a Solar Horizon Calender. This means that a distinctive horizon is either found (natural landmarks, etc) or created (such as Chankillo's case, with the man-made towers). The horizon is then used to mark specific alignments with the sun in the sky for whatever reason, be it religious, or just to mark when the harvest should be. In Chankillo's case, it is more than likely religious, as well as social, but I'll get to that later.

Specifically, it is a Solar Horizon Calender. This means that a distinctive horizon is either found (natural landmarks, etc) or created (such as Chankillo's case, with the man-made towers). The horizon is then used to mark specific alignments with the sun in the sky for whatever reason, be it religious, or just to mark when the harvest should be. In Chankillo's case, it is more than likely religious, as well as social, but I'll get to that later.Chankillo has four major components.

They are: 1) The fortified temple you see up in the top left of the photo, 2) the western (known as the sunrise spot, because you can see the sunrise from there) observation point and complex, 3) the actually 13 towers, and 4) the eastern (sunset) observation point and "party" complex. The fortified temple Dr. Ghezzi didn't really talk about, except to point out that there were big fortifications around it, which is a little unusual for just a temple complex. The Western Observing point is pretty interesting. It consists of a building with 18-foot tall walls around it, a narrow passageway on the south side of the complex which opens up into a three-foot tall wall area. From there you can see the towers. This is the observatory. On the Eastern side, the observatory is less well preserved (surprising, especially since the west side was almost obliterated by a massive flood), but you can make out the observation point. There is also a big complex just south of it where they uncovered offerings of shells, vessels (for beer and stuff), and little pipes (like musical instruments). This side is for the common people, where the celebrations were held, and the reason the West side is so fortified is because it was for the social elite. On the west side there were found "warrior figurines"-- clay figures with fancy nose, chest, and neck jewelry. These guys were not just pawns you put at the front of the battle to get killed off, they were important people. Only they were allowed on the west side of the complex. They were special.

They are: 1) The fortified temple you see up in the top left of the photo, 2) the western (known as the sunrise spot, because you can see the sunrise from there) observation point and complex, 3) the actually 13 towers, and 4) the eastern (sunset) observation point and "party" complex. The fortified temple Dr. Ghezzi didn't really talk about, except to point out that there were big fortifications around it, which is a little unusual for just a temple complex. The Western Observing point is pretty interesting. It consists of a building with 18-foot tall walls around it, a narrow passageway on the south side of the complex which opens up into a three-foot tall wall area. From there you can see the towers. This is the observatory. On the Eastern side, the observatory is less well preserved (surprising, especially since the west side was almost obliterated by a massive flood), but you can make out the observation point. There is also a big complex just south of it where they uncovered offerings of shells, vessels (for beer and stuff), and little pipes (like musical instruments). This side is for the common people, where the celebrations were held, and the reason the West side is so fortified is because it was for the social elite. On the west side there were found "warrior figurines"-- clay figures with fancy nose, chest, and neck jewelry. These guys were not just pawns you put at the front of the battle to get killed off, they were important people. Only they were allowed on the west side of the complex. They were special.Anyway, so what's so special about Chankillo? Why is it interesting? Well, there are thirteen towers. From the east side observatory, on can only see 12 towers, since the last couple move towards the west and actually overlap just enough to make the last one unviewable from the east. On the west side, all thirteen can be seen, but a mountain, known fondly as Cerro Mucho Malo, appears in the distance just to the left of the first tower. What is it? A natural 14th tower perhaps? It appears so. Dr. Ghezzi did a study of mapping the sun throughout the year in reference to the towers. What did he find?

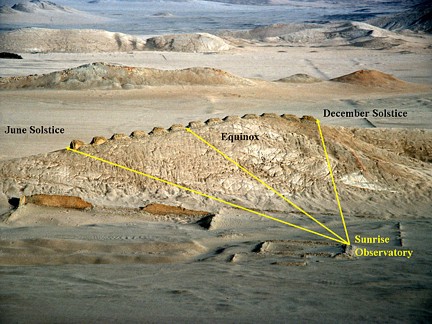

That at the west side, the June solstice was marked between the mountain and the first tower, the December solstice was marked just to the right of the 13th tower, and the Equinox was marked dead center. Interesting! And, so you know, the June solstice was the time of the Incan Harvest Festivals.

That at the west side, the June solstice was marked between the mountain and the first tower, the December solstice was marked just to the right of the 13th tower, and the Equinox was marked dead center. Interesting! And, so you know, the June solstice was the time of the Incan Harvest Festivals. (This is the sun rise on the day of the June Solstice--you can see ol' Cerro to the left there...)

(This is the sun rise on the day of the June Solstice--you can see ol' Cerro to the left there...)The sun takes about 10 days to move from tower to tower, but spends about 2 weeks on both the first and last towers. So in a way, it's a bit like a calender with a 10-day week. Every now and then there is some time left over that needs to be accounted for, so that is why the thirteenth tower is there (this part I don't really understand, because what about the mountain? Is it optional because it isn't part of the physical complex?) which can act like our modern Leap Day. Somehow.

Anyway, so what if it's cloudy one day? Everyone knows that Peru's coast is consistently covered with fog and cloud cover (okay not everyone, but now you know). The valley this place is on the edge of has two rivers that empty into the ocean. I'm not really sure how any of this works actually, but basically the clouds stay in the valley for some reason and don't come up to the ridge where Chankillo is. Chankillo is known as the "Place of Eternal Sunshine" or something fancy like that. But basically, it never gets cloudy. But the rivers are there too, so it's a greatly abundant area. Perfect for the Inca to settle down in.

Well, that's basically it. It was a pretty interesting lecture, like I said, and it was nice to get out of the heat for a couple of hours. I think it got up to 101 or something on Friday.

1 comment:

interesting. what about chichen itza? does that count? cos I know that the snakey dude thing goes up or down the main tower thing when it's time to plant or harvest the crops or something... yeah that was vague. also, I don't know if I get what your text was about on Friday. But I can't remember and I've had to delete it- so that may be part of the problem.

Post a Comment